A brief history of BBVA (I): The founding of the Banco de Bilbao

This article is the first of a series that will focus on BBVA’s long history. Over a number of chapters, bbva.com wants to recap some of the highlights of the bank’s almost 160 years of activity, thanks to which it has become one of the most renowned institutions throughout the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries.

By the mid-19th century, Spain was undergoing a period of profound change that resulted in political turmoil. The Corporations Act had been enacted in the 1840s and the thriving mining industry demanded better transport infrastructures and better financing options. With the arrival of the liberal revolution, the scenario for banking institutions took a radical change for the better.

In 1837, Spain, opened the first railway line of its history, which was not built in the peninsula, but in Cuba. It was the Havana-Güines railroad. It would take the country another ten years to complete its first peninsular line: Barcelona-Mataró. The next one was the Madrid-Aranjuez line, followed by the Langreo-Gijón line, which arrived to the port in Asturias in 1954.

On June 3, 1855, the progressive government managed to get the Parliament to approve the Railway Sector Law, which established the development of the railway lines in Spain by means of public concessions to private institutions. Within this mixed model of public support and private investments, the radial layout of the future network was defined, with lines departing from Madrid and arriving to the country’s main sea ports or border crossings. The passing of the law paved the way to a decade-long boom during which 5,000 kilometers of tracks would be built, laying bare the need for a fluid financing system in the country.

On January 28, 1856, the so-called Banking Law was published, after 6 months of hard work during the second half of 1855. This new regulations still envisaged the existence of issuing banks, up to one per city, and turned the Banco Español de San Fernando – resulting from the merger of two issuing institutions such as the Banco de San Fernando and the Banco de Isabel II – into Banco de España. Thus, 18 new issuing banks were created in Spain, on top of the new Banco de España and the banks of Barcelona and Cádiz, which already existed at that time.

Also, the law of 1856 established the regulatory framework for credit institutions, non-issuing banks engaging mainly on lending and discount practices. Credit institutions were born with the purpose of attracting the savings of the Spanish people and lending them to the industry. Essentially, to the burgeoning cash-hungry railway industry. Credit societies started popping up in significant numbers after the new legislation was enacted, reaching a total of 35 plus two other institutions specializing in money orders.

View of Bilbao (etching), by Percival Skelton. Mid 19th Century

Banco de Bilbao, the beginning of the future BBVA

The entrepreneurs that in the 1850s made up the Board of Trade of Bilbao were quick to react to the passing of the Issuing Bank Law of 1856, in an attempt to boost activity within Bilbao’s industry. Back then, Bilbao, with a population of barely 18,000, was a city under the influence of the wave of romanticism that swept across Europe. By the end of the 20th century, the city had grown to over 400,000 inhabitants.

Three weeks after the approval by of the law by the Parliament, Pablo de Epalza, Chairman of the Board of Trade, encouraged other board members to establish a commission to assess the incorporation of a bank in Bilbao. On March 7, the intervening parties were summoned to the reading of the report that had been drawn up for such purpose, whose contents were enthusiastically received by the members of the Board of Trade of Bilbao. One week later, an application was filed requesting the civil governor of Vizcaya to authorize the incorporation of an issuing bank in Bilbao. The name chosen for the bank stated in the application, which was enclosed with a plea to Queen Isabel II, was Banco Bascongado. However, that name was also stricken in the document, and replaced with Banco de Bilbao.

On April 29, 1856, the founders of Banco de Bilbao formalized the incorporation of the institution by means of a deed filed with notary public Serapio de Urquijo “for the founding of a privately-owned bank for the conduction of banking activities, including banknote issuing, discounting securities, processing of money orders and make loans, called Banco de Bilbao. Upon completing the cumbersome administrative procedure with the Civil Government of Bizcaya, calling of the General Shareholder’s Meeting, approving of the deed of incorporation and formalizing an additional deed, the Royal Decree of approval of Banco de Bilbao was published in La Gaceta de Madrid, one year later: May 28, 1857.

Banco de Bilbao was born with a permit that was valid for an initial 25-year period, starting on the date of its legal incorporation, with a social capital of 8 million reales, divided into 4,000 shares of 2,000 reales each. This founding social capital allowed the institution to issue banknotes up to 24 million reales. The founders of the bank were 106.

Banco Bilbao’s journey as financial institution started on August 24, 1857, in its humble headquarters in number 7 of the then-called Estufa Street. Carlos Adán de Yarza was the major of the city.

The founding Board of Directors consisted of:

Ambrosio de Orbegozo, director

Pablo de Epalza, member

José Pantaleón de Aguirre, member

Mariano de Zabálburu, member

Gabriel María de Ybarra, member

Felipe de Uhagón, member

Benito de Escuza, member

Vicente de Arana, member

Pedro Antonio de Errazquín, member

Luis de Violete, member

Ezequiel de Urigüen, member

Francisco Mac-Mahon, member

Leonardo de Lanzázuri, secretary

Santiago de la Azuela, Royal Commissioner

List of share underwriters at the time of incorporation of Banco de Bilbao - Archivo BBVA

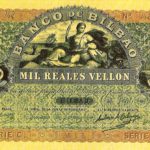

Despite being initially incorporated as issuing bank, Banco de Bilbao’s first steps borne witness to its clear vocation as commercial and investment bank. Also, instead of rushing to issue the 24 million reales for which they had been authorized, the bank only issued 6 million, in what was a clear exercise in caution. Six series of 100, 200, 500, 1,000, 2,000 and 4,000 reales were issued.

Seeing that the institution’s good work during its first few years of existence was being recognized by the State Administration, the board members of Banco de Bilbao had covered the issue of the 24 million authorized by 1861, just four years after being founded. Thanks to the trust that it had earned, it did not take long for the central government to increase the aforementioned limit to 30 million reales.

Banco de Bilbao backed many of the initiatives that launched in Vizcaya. Businesses such as workshops, family-owned enterprises, shipping lines, forges, railways, the port and the iron ore mines, were just a few of the enterprises that earned the financial institution’s trust.

It can be said that there were virtually no local initiatives that were not served by the young banking institution. Finally, it is worth noting that, just as in Bilbao, the new issuing bank law promoted the incorporation of issuing banks in other major cities across Spain such as Seville, Valladolid, Malaga, Saragossa, Santander and La Coruña. The prominent locations that did earn approval to incorporate a new bank were serviced by branches of Banco de España.

1,000 reales de vellón banknote issued by Banco Bilbao in 1859

Sources:

- 'La Banca como motor de desarrollo en España: 150 años de historia bancaria, 1850-2000' (The banking sector as driver of development in Spain: 15o years of banking history, 1850-2000). Author: José Víctor Arroyo Martín

- 'Un siglo en la vida del Banco de Bilbao. Primer centenario (1857-1957) (A century in the life of Banco de Bilbao. First centenary (1857-1957)'. Several authors

- 'Cientocincuenta años, cientocincuenta bancos (a hundred-and-fifty years, a hundred-and-fifty banks)'. Authors: Manuel Jesús González, Rafael Anes and Isabel Mendoza