Where have all the women gone?

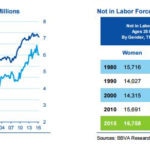

Alarming numbers of both men and women of prime working age (25-54 years old) have been exiting the labor force. There were 4.3 million more prime-age working people who opted out of the workforce in 2016 compared to 2000. The number of males age 25-54 not in the labor force has been increasing since the late 1970s, but the same couldn’t be said of females until 2000. What is behind this historic break in the female labor force trend? To properly analyze the female labor force, it needs to be separated into different cohorts — married vs. unmarried, with children vs. without — since each of these groups exhibits different employment patterns and wage change.

For example, the majority of the decline in the female labor force is among unmarried women and those without children. For these groups, wage decline is a dominant factor in explaining their exit from the workforce. Additionally, both young and less educated women are more likely to drop out of the workforce than older and more educated women regardless of their marital status. For mothers, income levels can increase or decrease their odds of opting-out of the labor force after childbirth. Women with annual household income below $50,000 are the most likely to opt-out. One explanation is that these women have to forgo less when exiting the workforce. When childcare costs and other household expenses are high, in other words, they are “unable to afford work.”

The question remains: Can we bring women back into the labor force? First of all, do the women who currently opt-out even wish to return? Recent surveys indicate that as many as 42% of women who are “homemakers” would currently consider a full-time or a part-time job, which has positive implications for the future of female labor force growth. However, as the reasons for opting-out diverge depending on income, race, education, marital status and motherhood, the prescription to reverse the decline in the female labor force is not straightforward.

Corporations can play their part by ensuring wage growth, gender wage equality, equal opportunity in promotion tracks and time flexibility, which play important roles in keeping highly educated, prime working age women in the labor force. With policies such as generous parental leave, compressed workweeks, telecommuting and job sharing, the IT and health care industries have pioneered measures to promote gender equality and retain their female workforce. However, corporate policies need to be more expansive to include less educated workers, who are at greater risk for dropping out of the labor force.

The U.S. ranks 25th highest for female labor force participation — a dramatic decline from 1995 when it ranked 7th

Government policies and spending also have room for improvement. Right now, among countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the U.S. ranks 25th highest for female labor force participation — a dramatic decline from 1995 when it ranked 7th. Fellow OECD countries like Denmark and Sweden offer prime examples of successful early education and childcare initiatives as well as implementation of family-friendly policies, such as generous paid leave for both parents and flexible work options. In the U.S., the introduction of policies that promote the dual-earner model and an increase in public child care expenditures should help to increase female labor force participation across all cohorts. The reentry of these lost female workers into the labor force will boost GDP growth and impact future price and wage inflation, and can have positive repercussions, such as higher living standards and wider opportunities, for women’s partners and children.

Any statement or opinion of an economist affiliated with BBVA Compass is that economist’s own statement or opinion and does not represent a statement or prediction by BBVA Compass, its parent companies or management.